Sale on canvas prints! Use code ABCXYZ at checkout for a special discount!

Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) has a special place in my heart because it is the first wildflower I see every spring. It flourishes in a shady corner of our backyard near the bend in the stream. In late April or early May I find it covering last year’s dry brown leaf litter with a carpet of pure white stars.

A member of the poppy family, bloodroot is well named. The sap in the roots and leaves is a startling scarlet color. I accidentally broke the bud off of a small stem with my clumsy boots when I was photographing the flowers, and was aghast at the gory results. The stem immediately began to ooze brilliant drops of red. I understand that native Americans used it as a dye and also mixed it with animal fat for body paint. Dry, the juice looks exactly like a bloodstain.

Native Americans also used this plant for its medicinal properties. In the hands of a good medical practitioner, bloodroot can be a potent medicine, but it is not one for amateurs. It contains opium-like alkaloids and can be deadly if taken internally or leave scarring if used externally. For this reason it is considered toxic.

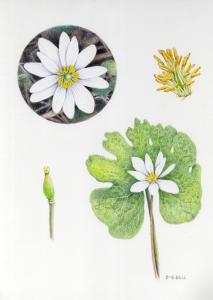

Bloodroot is a very simple and economical plant. Each consists of one leaf and one flower stalk. They only open their blooms on warm, sunny days. The plants work their way out of the ground well-protected from the harsh spring weather they face. The flower bud is covered by a pale green pair of sepals and completely wrapped in the large lobe-edged leaf. The sepals fall off as the flower opens. Even after the flower is open, the leaf still wraps shelteringly around the stem. On a cold cloudy day they look like a company of star-people with blankets wrapped snugly around their shoulders.

Bloodroot is an ephemeral spring star. The blossoms last only about a week. Insects to pollinate the flowers can be scarce in the early spring, but that does not matter. For the first two days after the flower opens, the stamens are close to the petals and do not contact the stigma, even at night when the flower is closed. But on the third day, the anthers are positioned upright and the filaments bend inward, so that the plant will self-pollinate if it has not already been pollinated by an insect.

After the petals fall, the leaf continues to grow, and can be as large as eight inches across at full size. The veins of the leaf show clearly in a complex network pattern. The top side of the leaf is bright green and the underside a dull grayish green.

The seed pod develops at the top of the stem that held the flower. The plants spread by seed and also from the roots. Bloodroot plants have a fascinating relationship with the ants that live among their roots. The seeds carry an appendage called an elaiosome that is a very nutritious food source for the ants. The ants collect seeds, carry them home, and eat the elaiosomes. Then they discard the rest of the seed, still intact, in their refuse tunnels, where the seeds eventually sprout and grow. This mutually beneficial relationship between the ants and the plants is called “myrmecochory;” the ants get the food and the bloodroot seeds are preserved and given an ideal environment for germination, which produces more food for the ants.

Bloodroot thrives in semi-shaded conditions, in moist woods with acidic soil. Most of the bloodroot currently used for medicinal or landscaping purposes is “wild-crafted,” that is, grown in the wild and harvested by herb collectors. Since the demand is greater than the supply, some are experimenting with growing it commercially on a small scale.